History and harmonious connections

Members of the Indiana University delegation began day two of their weeklong trip to Germany by traveling to Berlin’s oldest university, where they glimpsed several new possibilities for strengthening IU’s already deep connections with one of Europe’s most dynamic cultural, economic and political centers.

The Humboldt University of Berlin in Mitte, Berlin’s most central borough and one of two boroughs that span the former east and west districts of the city, was founded in 1810 as the University of Berlin, just 10 years before IU’s inception, by the Prussian philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt. In 1949, it was renamed Humboldt University in honor of Wilhelm and his brother, Alexander, a geographer and explorer.

Today, large marble statues of the two brothers adorn the entrance to one of Europe’s most prestigious universities and one of the world’s most acclaimed centers for education in the arts and humanities. HU, a research-intensive university that has served as a model for several major American higher education institutions, has educated 29 Nobel Prize winners and counts among its scholars and students a who’s who roster of history’s foremost thinkers, including Albert Einstein, Otto von Bismarck and Karl Marx.

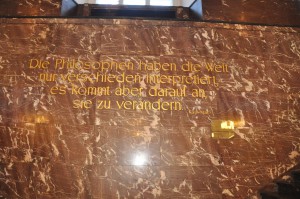

A quotation from Marx greets visitors to the main HU building, a former palace of Prince Henry of Prussia (1726-1802). Affixed to the wall in golden letters, it reads: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point however is to change it.”

The quote, along with signs on the main entry staircase reading “Vorsicht Stufe,” or “Mind the Step,” reflects HU’s main mission as well as its turbulent history. In the early part of the 20th century, HU gained a reputation for shaping the minds of many of Germany’s greatest thinkers and scientists, but like all German universities after 1933, it was seriously impacted by the Nazi regime. Under Nazi rule, hundreds of Jewish professors and employees at HU were fired, and students and scholars opposed to the Nazis were expelled and sometimes even deported. Additionally, tens of thousands of books from the university’s library were burned.

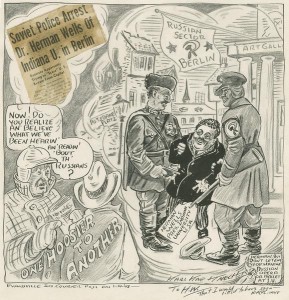

After World War II, the university “reopened” in the Soviet zone of East Berlin once again as the University of Berlin, but now based on a communist model of teaching. The new university was but a shell of itself, with many of school’s former teachers having died or gone missing during the war and its buildings enduring massive damage. Scholars opposed to the school leadership were arrested or deported, thus leading to the movement for a “free university” in Berlin, an effort with which IU’s legendary 11th president Herman B Wells became intimately involved. In 1948, the Free University of Berlin was established.

More than four decades later, following the unification of East and West Germany, the university underwent another major restructuring and renewal process. In the early 1990s, all of the school’s faculty members were dismissed. A third were rehired, thus beginning a lengthy growth process that has taken the better part of the last two decades.

Once again known as Humboldt University, the institution currently educates more than 30,000 students, including 6,000 international students, across nine faculties, or schools. HU and the Free University also jointly operate the largest medical school in Europe, and HU possesses celebrated strengths in, among other areas, law, mathematics, the life, natural and social sciences, and the humanities.

In 2012, HU was one of 11 German universities to win funding in the German Universities Excellence Initiative, a national competition for universities organized by the German government that aims to promote innovative research, strengthen global research cooperation and enhance the international standing of German universities. The award arrived just two years after HU celebrated its bicentennial and began ramping up its effort to become one of the world’s top research universities, one that bridges the traditional divide between the natural sciences and the humanities, while also providing students opportunities to experience other cultures around the globe.

Those back home in Indiana familiar with IU’s new strategic plan as the university fast approaches its own bicentennial (in 2020) might already have picked up on the major similarities between Indiana’s flagship institution and HU. As IU President Michael A. McRobbie explained to the delegation’s hosts, which included HU’s vice presidents for research and academic and international affairs, IU has undergone its own extensive restructuring and renewed its commitment to greater internationalization. This effort has resulted in the establishment of seven new schools, including the School of Global and International Studies; around 8,500 international students annually, about 50 of whom are German; graduating classes with roughly 30 percent of study abroad participants; and three new global gateway offices, including one in Berlin, the IU Europe Gateway, that will be formally dedicated Thursday.

Members of the IU delegation, seated at table on right, meet with senior officials at Humboldt University.

Furthermore, IU has just embarked on its own “excellence initiative” of sorts: a Grand Challenges research program that will lead IU to invest nearly $300 million over the next five years to develop transformational solutions to some of the world’s most pressing problems. The university plans to fund three to five projects between now and its bicentennial year.

As delegation member and IU Vice President for International Affairs David Zaret noted, IU and HU are both “proceeding along parallel paths” in terms of marshaling their scholarly talent to address major world challenges and engaging expertise in both their arts and humanities programs and their professional schools toward meeting their respective university’s lofty ambitions.

Today’s meeting between IU and HU officials generated a number of ideas for exploring potential collaborations between IU and its forthcoming work on Grand Challenges and HU’s ongoing effort to meet the goals of Germany’s Excellence Initiative. Both schools’ officials also recognize the importance of increasing the number of students who study abroad, thus exposing them to other economies and cultures. (About 100 IU students study in Germany each year.)

Indeed, fostering greater multicultural understanding is of great concern in Germany, which, according to recent reports, will take in over a million asylum seekers this year, including thousands of Syrian refugees. As IU President McRobbie commented, IU also has a responsibility, as the state’s flagship university, to diversify its campuses and broaden the global literacy of its students, an issue increasingly important as Indiana continues to experience a major boom within its Hispanic population.

Indeed, to borrow from one HU official, many “interesting connections” between IU and HU are already appearing on the horizon.

A potential creative and cultural collaboration

Harmonious would be a fitting adjective to describe the IU delegation’s final set of meetings of the day — with administrators and faculty at the Universität der Künste Berlin, or Berlin University of the Arts, the largest art and music school in Europe. In its three-centuries-old history, UDK has earned its place at one of the most highly respected arts institutions on the continent and also one of Europe’s most versatile such schools, uniting four colleges specializing in fine arts; architecture, media and design; and music and the performing arts. It is also one of Berlin’s most active cultural centers, offering more than 800 events each year, including many at its College of Music, founded as the Royal Academy of Music in 1869 by Joseph Joachim, a friend of Johannes Brahms.

In news that shouldn’t surprise any Hoosier, IU and UDK had plenty to discuss. In fact, one wouldn’t need a creative arts degree to dream up possibilities for fruitful exchanges between the two universities, including any number of collaborative activities involving IU’s world-renowned Jacobs School of Music or its distinguished programs in Theatre, Drama and Contemporary Dance, Art and Design, Media and film studies.

IU President Michael A. McRobbie, second from right, tours the lobby of the performance hall at Berlin University of the Arts.

To that end, IU will soon sign an agreement of friendship and cooperation with UDK, and plans are already underway that could enable chamber-sized groups of IU Jacobs School students to showcase their musical talents here in Berlin, possibly at UDK’s impressive performance hall.

Personally speaking, I would enthusiastically applaud that idea, having viewed, first-hand in the spring, just how meaningful it was for IU student orchestra musicians to get to play at Seoul’s acclaimed Performing Arts Center.

In a little over 48 hours, IU will formally dedicate the new Europe Gateway office in Berlin, where today’s productive meetings offered further proof of IU’s remarkably strong connections with the city and the possibility for even greater engagement across Germany for years to come.

Tags: Berlin, Berlin University of the Arts, David Zaret, Drama and Contemporary Dance, Free University of Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin, German Universities Excellence Initiative, Germany, Grand Challenges, Herman B Wells, HU, Humboldt University of Berlin, IU Bicentennial Strategic Plan, IU Department of Theatre, IU Europe Gateway, IU Global Gateway Network, IU Media School, IU School of Art and Design, Jacobs School of Music, Michael A. McRobbie, School of Global and International Studies, UDK, Universität der Künste Berlin